Egyptian origins

The Egyptian origins of reflexology can be seen in a frieze at the tomb of Ankhmahor that is thought to illustrate a reflexology treatment taking place (figures 1.1 and 1.2). This tomb in Saqqara is known as the ‘physician’s tomb’ owing to the marvellous portrayal of many medical scenes found on its walls. The tomb was discovered by V Loret in Egypt in 1897. Saqqara is one of the richest archaeological sites in Egypt, containing monuments constructed over a span of more than 3,000 years, the earliest being the Mastabas, the earlier name for a tomb. Saqqara is the largest necropolis found (a large burial ground of the ancient city). Activity was extremely intense in this area during the Old Kingdom.

The Old Kingdom encompassed the period from the 1st to the 6th Dynasty when all the great pyramids were built in Giza and in Saqqara this period lasted from 3000 to 2250 BC when it came abruptly to an end, owing to a civil war breaking out, and the whole empire collapsed. To the Ancient Egyptians the afterlife was just as important as the earthly life, hence the reason they surrounded themselves with many murals and pictures on the walls of their many tombs; these portray agricultural scenes and abundant harvests as well as hunting, fishing and dancing scenes and many games. All of these were of an afterlife modelled on a visionary earthly life. Ankhmahor was an able master-builder and was considered an expert because he controlled the work of the many sculptors at the tomb. This project disclosed his keen interest in medicine as he displayed recurrent images of medical themes and surgical operations taking place on the walls. His interest in pathology was attributed to his admiration of another architect named Imhotep, who was made an object of worship and was later known as Imuthes, God of Medicine. (Imhotep built the first step pyramid for King Zoser the Pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty in 2686 BC when Zoser was the King of Upper and Lower Egypt.)

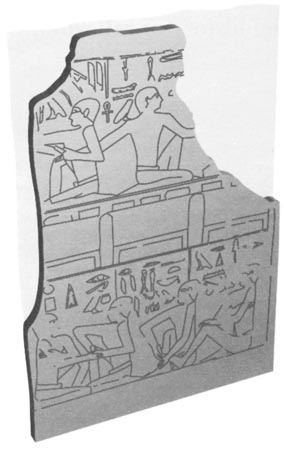

Figure 1.1 Illustration of patients having hands and toes treated (lower picture) and a patient having hand treatment (top picture), from the tomb of Ankhmahor.

In the Masataba of ‘Ankhmahor’ on the west door entrance are two registers representing the treatment of hands and feet. These are referred to as a manicure and pedicure by Alexander Badawy in his book The Tomb of Ankhmahor at Saqqara in which he gives a very fine detailed translation of the wall scenes. In one scene on the wall the right hand of one person is being treated and the other person is having a toe on the left foot treated. The text reads: (patient) ‘Make these give strength.’ The operator responds, ‘I will do to thy pleasure sovereign!’ (This answer is between the two operators, so it could be valid for both.) The patient who is having his toe treated is begging, ‘Do not cause pain to these.’ There also appears to be a probe in the operator’s hand (see figure 1.1) (although this is not shown in the many reproduced copies that are included in many reflexology books). An upper fragment on the same wall shows a patient having both hands treated; however, the inscription was badly defaced (see figure 1.1).

Figure 1.2 Patients having massage or manipulation of the foot or leg and shoulder, from the tomb of Ankhmahor.

Another relief shows massage or manipulation to the foot or leg and shoulder (figure 1.2), which could indicate some form of pressure therapy. As massage was often mentioned in many of the texts and old medical papyri it is quite reasonable to believe that this could be a form of reflexology treatment taking place on the hands and feet with massage or manipulation to the legs and back.

Ankhmahor himself is represented on two door-jambs in identical striding attitude. The inscriptions indicate the many titles he held; these include ‘Hereditary Prince’, ‘Count’, ‘Chief Justice’, ‘Vizier’ and ‘Court Physician’.

Данный текст является ознакомительным фрагментом.